Resources

Stay up-to-date with VetLed news and events, browse our blogs, download free resources, and follow our campaigns.

Many of us spend so much time at work that our colleagues feel more like family or close friends, especially when we take on the stresses and pressures of veterinary life together. This feeling of being 'in it together' can strengthen team bonds and provide comfort and support, but it can also make it easy to miss the signs that someone in the team is struggling.

My experience…

I’ve experienced my fair share of mental health challenges during my veterinary career – I embody the perfectionist streak that’s so common in our profession. When I graduated, I was suddenly blindsided by the feeling that I wasn’t good enough or didn’t know enough, so of course, I threw all of my energy into trying to make sure nobody found out! At a time when I was already under a lot of pressure to learn on the job, put my knowledge into practice, and learn new skills, it was tough keeping up the façade that I was coping… succeeding… and even enjoying it. After all, this was all I’d ever wanted to do and I knew I should be grateful.

It lasted all of three months. I broke down at a work social event and admitted some of my fears to a colleague. Since then I've received support in different forms, from colleagues, bosses, friends and family, and therapists. I've often felt much better, but I've also relapsed and had moments when those imposter thoughts would win and I'd feel like I was a new grad again, not someone with over ten years of clinical experience. It's a work in progress, but I could never have started if I hadn't opened up.

How to spot subtle signs that your colleague might need support

During those first three months, it wasn't obvious that I was struggling. I turned up and did my job well, I asked a few questions but was often self-sufficient, I shared jokes with colleagues, chatted about my weekend, and probably appeared to be doing just fine. No one could tell I was lying awake at night going over the cases I'd seen and whether there was anything I could have missed. No one saw me subtly checking all of the cases I'd seen when I was on call to make sure none had died and I did my best to hide the 'doom feeling' if I found one that had, while I frantically searched for clues about whether I was at fault or it was unrelated.

In such a high-performing career, it's natural that many fight to avoid showing signs of weakness. However, that does mean it's more challenging for the rest of the team to support them. So, what signs might suggest that a colleague is having a tough time personally or professionally?

- They’re not around for breaks

When things feel tough, it sometimes feels like all you can do is keep going. If you have a colleague who regularly works through their breaks, it could be a sign that they’re feeling overwhelmed. On the other hand, if a colleague usually spends their breaks with the rest of the team but they start choosing to be alone, this could be a sign that they’re struggling.

- Their timings change

When dealing with mental or physical health challenges, it’s hard work just getting out of the door in the morning. These issues can also go hand in hand with poor sleep, making mornings even harder. A colleague who is suddenly regularly late for work, or unusually early for work if they have been unable to rest and can’t switch off, may need some support.

- They’re picky about the work they do

This one I can personally relate to – when you’re a vet or vet nurse and feeling anxious, stressed, burned out, etc. you might start to protect yourself (consciously or unconsciously) by avoiding consults or surgeries that seem more challenging. It’s important to understand this because it’s easy, as a colleague, to become frustrated. After all, if a vet who you believe is more than capable appears not to be doing their fair share of the work, or leaving the harder bits for someone else, your initial assumption might be that they’re lazy, can’t be bothered, or don’t care about their colleagues. But what if there was another reason? What if they are just in survival mode?

How can you help a colleague who’s struggling?

Every relationship between two colleagues is different, and how you approach offering help and support will depend on your unique relationship. However, these tips could be useful in getting started:

- Ask ‘Is everything okay?’

Perhaps a good place to start is being gently curious when there's no one else around, without creating any pressure for them to share. You might find that they’re relieved to have been asked or that starting the conversation leads to more natural opportunities for them to share going forward. If 'Is everything okay?' seems too broad or pointed, consider a more specific conversational question like 'How was your day?' to get the conversation going.

- Let them know you’re concerned, without judgement

If they say everything’s fine or avoid the question, it might be appropriate to say you're concerned about them. Avoid listing specific observations as evidence if they could be interpreted as criticism, for example, ‘I noticed you were late today’ – letting your colleague know that they’re not managing to keep up appearances is likely to make them feel much worse. This could lead them to be more self-critical and worry more about what management thinks or their job security. Instead, identify yourself quickly as someone who cares and wants to help, then give them time to process.

- Share your own challenges

Sharing is hard, especially if it seems like everyone else is finding the job easy or taking it in their stride. Starting a two-way dialogue where you show your vulnerability and fallibility by sharing a recent case or situation that you found difficult could help you seem more approachable to your colleague.

- Work on whole-team wellbeing

As to whether you should or shouldn’t share your concerns for your colleague with your boss… for me, there's no clear-cut answer. Of course, if you are concerned for their safety or that of their patients, letting someone trusted in management know is probably unavoidable. However, letting management know if your colleague has confided in you could damage your relationship and prevent you from helping them further. Whether you share your specific concerns with your boss or not, suggesting that the practice clearly signposts support services like Vetlife and promotes team wellbeing by encouraging team members to listen to their needs, take time out when they need it, and share their struggles, will remove any stigma around needing help and benefit the colleague indirectly. You may do this by introducing wellbeing rounds, Schwartz rounds (after suitable training) or through wellbeing training, like ourHALT workshopsand HALT campaign.

Summary

It’s not always easy to spot the signs that a colleague is having a hard time, and even if you have a suspicion, trying to find the right words to get them to open up or accept support without causing offense or making them feel worse is another challenge. Look out for changes in their usual routine and behaviours, and let them know gently and compassionately that you’re concerned about them, without making them feel cornered or judged. Signpost sources of support, and if you have serious concerns for your colleague’s safety, speak to someone you trust in the management team.

Being a vet or vet nurse can feel draining. Yes, they're really rewarding roles and we get to make decisions, start treatments, and perform procedures that have a clear positive effect on the lives of animals. But the hours can be long and the pressure and responsibility high, and it’s particularly tough when the outcome for the patient doesn’t reflect our hard work. But it’s worth it, right? Because working in veterinary is something we always dreamed of.

But what if you have another dream? What if you’ve always seen yourself settling down and having children and a family life? Is that compatible with a fulfilling career in veterinary? Can you really have both?

Being a parent brings a mixed bag of rewards and challenges. Different life stages present various struggles, from the exhaustion from disturbed sleep from night feeds and co-sleeping in the early years, to the mental strain of organising childcare and travel to clubs and hobbies as children grow. All the while, you’re shaping a little person – doing your best to give them the best foundations for a good, happy life with healthy relationships.

Do you really have enough in the tank to pursue both dreams? Maybe, but it’s not easy.

It's unsurprising, then, that many vets and nurses who are also parents have poor wellbeing. After all, it’s easy to overlook our own wellbeing in any scenario, let alone when there are poorly patients or dependant little people demanding our time. So, how do we prioritise our wellbeing when juggling parenthood and a busy work life?

- Plan ahead

When life is overwhelming and you're busy, it can feel like you're just muddling through the days as best you can with no real plan. But planning for the week can give you a sense of control, helping you to identify any time-keeping issues in advance and keep things running as smoothly as possible. Of course, it takes a little more time at the start of the week, and things are subject to change. But if you have a vague idea of what you and your family are doing each day, you might feel a bit lighter because there are fewer worries causing background noise in your brain.

- Share the load

If you have a partner, family, or close friends to lean on, try to delegate some of the responsibilities. Having a shared calendar with your partner (or anyone else who's a big part of your family life) will keep them informed and involved in any problem-solving of clashing commitments.

- Be realistic

You’re just one person, and as much as you might strive to be SuperMum or SuperDad, taking on too much will only add pressure that you don't need. It's easy to feel like you should be giving more – staying longer at work to help a colleague or using your only half day to take your child on an amazing outing – but is that sustainable? Remember the importance of rest and that you can be more present for your children and patients when you're not feeling stressed, overwhelmed, and exhausted.

- Be prepared

Make taking a break as easy as possible by being prepared. I bet you’re used to packing a bag full of snacks and drinks for your child when you go out, but do you ever bring anything for yourself? Packing a few feel-good, energy-boosting snacks when you go out for work or recreation will mean you have no excuse not to take a few minutes for yourself – the food is there ready for you.

- Share your needs

If you’re regularly missing your breaks at work, working overtime, or missing your child’s bedtime, it’s time to speak to your employer. Think about what would make this period in your life easier for you, whether that’s a change in work pattern, reduced hours, or a commitment to regular breaks. Perhaps you’re a breastfeeding mum who needs regular time to pump. Whatever you need, start the conversation with your boss.

Of course, it’s also important to share your needs outside of work with your partner or family. If the parenting load feels unbalanced, or there’s just something you’d like more help with, speak to your support network and let them know how they can help.

- Seek support

It might feel like it, but you're not alone in your struggles. Parenthood is often depicted as a highlight reel, full of rewarding and treasured moments and without any of the tantrums, arguments, and challenges. If you're finding it hard, you're not failing. You're not ungrateful. There's nothing wrong with you, nor your child/children. You're doing your best and you're doing a great job. Don't be ashamed to be open with your partner, family, and friends, or reach out to your employer or GP. Often, some of the best support comes from other parents who can really relate, so why not speak to friends who are parents or look for groups for parents in your area?

- Allocate time for you

Time for yourself might feel like it’s way down your list of priorities, but should it be? Remember, we can’t care for others, whether our patients or our families, on an empty tank. What makes you feel replenished? It's different for everyone and changes depending on the situation. Perhaps right now you need rest, or maybe you need quiet time to read away from the sensory overload of barking dogs or screaming children. Or are you craving the opportunity to do something you enjoy, a hobby or activity that's been neglected due to lack of time? It's not selfish to take time for yourself. Creating a regular slot where you do something for yourself will promote your sense of self and give you something to look forward to.

- Be kind to yourself

Above all, be kind to yourself. Life is messy and, even with the best intentions, there'll be times when your wellbeing drops off your radar. Don't use this as an opportunity to make yourself feel bad. The most important thing is to keep trying to create good habits that promote your wellbeing, so focus on the steps you've taken and how far you've come, not on the occasions when a busy life got the better of you.

Need more help?

VetLed’s HALT campaign is creating waves in the veterinary profession as it aims to make meeting our needs the norm in every practice and organisation. Resources like practice posters and information sheets act as great reminders and conversation starters. We can also provide HALT training workshops for your team, where we share the impact of poor wellbeing on patient safety (and our own health) and explore strategies to make wellbeing a priority within your team.

Flexee Vet is constantly working to promote flexible working for vets and nurses. Check out their social media for tips and support for making flexible working a reality.

Introduction

In this second blog, we will build on veterinary identities learning to offer practical steps to raise awareness of and challenge unhelpful professional discourses and improve workplace culture and the everyday lives of vets in practice. We will also discuss how we can support vets struggling with flawed versions of who they are.

Professional discourses

Images of the ideal vet can be hugely beneficial for aspirational vets to aim for in their identity work. Ideals spur vets on to learn and grow as clinicians and to do their best for their patients and clients. The construction of preferred identities is also associated with feelings of happiness, self-assurance and pride. However, strong collective understandings of what makes a perfect professional can have a detrimental effect as vets encounter real-world cases that do not respond as expected, critical colleagues, and challenging clients. Vets talk of how the extremes of vetting can lead to widely varying emotions ranging from euphoria and gratification to devastation, guilt, and shame. Recognising professional anxieties and challenging attachment to veterinary ideals may help the profession and organisations better support vets to manage the highs and lows of their everyday lived experiences and so better manage their mental health.

The profession is changing and now talks more openly about veterinary error and promotes no-blame learning environments, but there is a persistence to inherent discourses of perfection and those that say ‘good’ vets do not make mistakes. We can assist by calling out these implicit assumptions and encouraging professionals to ask for and offer help following veterinary mistakes. We can also actively engage with, rather than distance ourselves from, those constructed as flawed vets, so people don’t feel isolated after making mistakes.

Easing the transition from university to practice

We may be able to assist with the transition from university to practice by introducing uncertainty into scientific teaching to help vets better cope with inevitable real-world incidences where presentations do not match textbook descriptions and animals do not respond or recover as expected. The anxiety created by assumptions of perfection, belief in idealised veterinary images, and the consequent dread of the imposition of ‘bad vet’ identities can lead to recent graduates struggling with decision-making for fear of doing something ‘wrong’. Increased comfort with uncertainty and unpredictability may assist individuals to step back from unexpected outcomes, ask for help, assess the case with colleagues, learn and move forward.

More experienced vets can also play a part by recognising and challenging their own and others’ behaviours emanating from the formation of preferred identities. Identities are inherently fragile, so comparing oneself to others who may be viewed as less experienced, knowledgeable or competent and incorporating those assessments into identity stories is universal. It is the language and behaviours experienced by others as denigrating that can cause harm, not just to those who are the object of the comparison, but also those who witness it, and this can be reflected on and adjusted. By extension, if you have experienced a colleague’s demeaning behaviour at work, it may help to know that this conduct likely stems from the comparator’s insecurity rather than the subject’s professional (in)adequacy. Knowledge of this type of comparative identity work may assist with viewing challenging behaviours in a different light and open up a wider range of opportunities for working with individuals to effect change.

Adjusting behaviours to be more collegiate and supportive has the added benefit of improving psychological safety and encouraging less experienced others to more readily ask for advice and guidance because they are less likely to be concerned about appearing ‘stupid’ or to form a flawed identity (and experience the associated anxiety and distress). The likelihood of adverse events may also be reduced as veterinary colleagues work together to solve problems, ensure the health and welfare of animals, and take better care of themselves and each other.

Managing veterinary errors

Dominant discourses within the veterinary profession may underpin the dichotomy of externalizing or internalizing blame for veterinary mistakes. Recognizing the conflict between the historic discourse of individual responsibility and the need to apportion blame versus the contemporary professional commitment to no-blame learning environments may assist vets to respond to mistakes more productively and to feel less isolated. Dismissing mistakes as emanating from external factors beyond the vet’s control or constructing them as a demonstration of innate personal failing may lessen the opportunity to learn. Whereas if we step back, complete a human factors assessment and recognise contributing elements, we can approach learning collectively and take steps to make practical changes to systems, processes, and environments to reduce the likelihood of future mistakes. We can also support each other to repair preferred identities rather than maintain flawed versions of ourselves.

Concluding thoughts

Hopefully, this second blog has provided food for thought on challenging unhelpful professional discourses, the impact identity work can have on colleagues, learning from veterinary errors, and how we can better support one another to repair preferred identities and manage flawed ones. Not only will changes in professional and workplace culture assist vets to manage everyday work experiences more effectively and improve their mental wellbeing, but it will also benefit the animals they treat, the clients they serve, and the businesses they work for.

If you’d like to discover more about how you can adapt the way you work as a team to make mistakes less likely, look out for tickets for the next Veterinary Patient Safety Summit, happening in 2026!

You can also join our monthly Patient Safety CPD meetings - the Veterinary Patient Safety Forum. This free event is online on the first Thursday of every month. Find out more here.

Introduction

In this mini-series, we’ll first explore the link between veterinary error and identities. By learning how error narratives are incorporated into identities, we can better understand how we become the people we are and why we feel the way we do about errors. In the second blog, we will discuss what we can do from a practical perspective to support ourselves and others in recovering from difficult experiences. The findings described herein are taken from an empirical study into veterinary identities.

Veterinary identities

Vets, like other professionals (e.g., academics, doctors, priests, airline pilots), often speak of the centrality of work to their identities, incorporating what they do into who they are, making it hard to separate oneself from one’s work. Identities can be thought of as subjectively constructed through the stories told both in monologue and to others with oneself as the central character. In this context, identities are the meanings individuals attribute to themselves when answering questions such as ‘who am I?’. Identities are never fixed or complete; they are continuously worked on (to a greater or lesser extent) – a process known as ‘identity work’ – as individuals form, strengthen, maintain, repair, and revise who they are through telling and re-telling self-narratives over time.

Identity narratives are not formed spontaneously but are drawn from occupational discourses – the images, descriptions, assumptions, and stereotypes that make up our collective understanding of what makes (for example) a ‘good’ or ‘bad’ vet. To illustrate this point, picture for a moment what you understand to be a ‘good’ vet. Your understanding may correlate with other vets who, when constructing preferred identities, often talk about themselves as competent, hardworking animal lifesavers and fixers who are respected by colleagues and much-loved by clients. In comparison, if you imagine a ‘bad vet’, you might identify with vets who talk of their flawed identities as lazy, incompetent animal harmers and killers who are denounced by colleagues and unappreciated by clients.

The prominence of idealised veterinary images means that vets often believe perfect identities are achievable/achieved by others. Consequently, it can be difficult to navigate experiences that suggest imperfection. Younger vets in particular can struggle with the tension between aspirational ideals of perfection and the impossibility of ‘being’ perfect. As a result, they may experience considerable anxiety and insecurity. Individuals may worry that they are not (and may never be) good enough professionally (or even personally).

Veterinary error

The assumption that making a mistake is synonymous with failure, litigation, and being ‘struck off’ is common to vets and doctors. Despite advances in how veterinary errors are depicted, vets can draw on historic discourses, for example, that good vets don’t make mistakes or that veterinary errors result from personal failings. Veterinary errors can take many forms, including mistaken or missed diagnoses, patient morbidity or mortality, or medication errors. When they occur, vets can experience a multitude of feelings, including fear, self-doubt, inadequacy, vulnerability, distress, guilt, sadness, shame and isolation as colleagues distance themselves from error making others.

Some vets say they externalise blame by utilising defensive identity work strategies to distance from error-making identities, including denying mistakes happen or suggesting inferior vets make mistakes in comparison to their perfect selves. Others draw on discourses of human fallibility and suboptimal circumstances, blame clients and colleagues for mistakes, construct mistakes as recognized complications, or reassure themselves that the animal would have died anyway, or that a worse mistake could have been made.

In contrast, other vets say they maintain flawed identities, particularly following veterinary errors that lead to animal death, and above all, unexpected (anaesthetic) deaths. Some vets state they find it difficult (or impossible) to move on from mistakes, perpetually re-living the incident in their minds, whilst others say they will vividly remember mistakes (including the names of associated animals and clients) for the rest of their lives. Whilst those who employ strategies to distance themselves from mistakes appear better able to move on, those who maintain flawed identities talk of experiencing significant distress and mental ill health, including suicidal ideation.

Even when mistakes have not occurred, some vets describe catastrophising about imagined errors and routinely accessing the practice management system or phoning the duty vet from home due to the fear that a patient’s condition may have worsened (even when procedures have gone well). Some speak of waking up following work-related nightmares or convinced they have done (or not done) something terrible or that an animal they treated during the day has died.

Insecure identities

Because identities are continuously worked on, they are inherently insecure. Consequently, when working on preferred identities, some vets talk disparagingly about others (characterised as ‘lesser’ individuals) to construct stories of themselves as ‘good’ or better vets in comparison. Conversely, when working on flawed identities, vets often compare themselves to others they feel are more competent and worry about what colleagues think of them. This is especially noticeable in environments that people experience as competitive or judgemental. Knowledge of how identity work influences interpersonal interactions can help us understand why some people display challenging behaviours at work and recognize the impact of underlying assumptions, beliefs, attitudes and feelings on workplace culture.

Concluding thoughts

Hopefully, this brief review of veterinary identities has struck a chord with readers. In the second blog, we will explore how we can leverage our understanding of identity work to provide practical tips on supporting vets to manage everyday work occurrences and to repair preferred identities following difficult experiences.

If you want to explore veterinary error and patient safety further, join VetLed's free, monthly online CPD meetings - the Veterinary Patient Safety Forum

VetLed will also return with another Veterinary Patient Safety Summit in 2026 - watch this space for more details!

Are you new to a leadership role?

Or do you know you could do a better job with the right tools and support?

Our first Open Leadership Programme begins on 10th December! (with an optional Welcome Session on 12th November)

Just like our existing Leadership Programme, this is an 8-module, 8-month programme focusing on topics like giving and receiving feedback, compassionate communication, decision-making, and impacting workplace culture (for the better!).

However, now you don't need to wait for your boss or other leaders in your team to be eager and engaged, ready for an in-practice course!*

Instead, you can join like-minded leaders from other practices who are focused on developing their leadership skills to help them feel more comfortable and effective in their role.

This programme is delivered completely online, with live sessions and pre-recorded content, as well as paired reflective exercises.

Our monthly sessions will be on Wednesdays at 10am UK local time, and we'd advise not missing more than two of them (not including the welcome session in November). Click the button below to book your place before 31st October.

*That's not to say it wouldn't be great to do it with a colleague for maximum impact on your team! So, if you have a small group who'd like to join together, that's fine too!

BOOK YOUR PLACE NOW

The Veterinary Patient Safety Summit 2025 took place at Consort E3 at Harper and Keele Vet School on 17th October. It was a sold out event, full of passionate patient safety advocates. In November's Veterinary Patient Safety Forum, we'll share insights from the day that you can bring to your team. Join us online at 1pm local UK time for this free monthly event.

What are the aims of the Safe To Speak Up campaign?

To raise awareness of the importance of psychological safety in veterinary practice.

To enable all members of the veterinary team to encourage Psychological safety and embed it into the organisational culture of veterinary practices so that every one feels SAFE TO SPEAK UP.

What is Psychological safety and why is it important that we feel safe to speak up?

Psychological safety is broadly defined as a climate in which people are comfortable expressing and being themselves, more specifically when people have psychological safety at work they feel comfortable sharing concerns and mistakes without the fear of embarrassment or retribution. They are confident that they can speak up and won’t be humiliated, ignored or blamed. They can ask questions if they are unsure of something.

Psychological safety has been identified as key differentiator between higher and lower performing teams in studies of professionals in a variety of industries. ” It was identified by Google at the most important aspect of building a successful team as part of a two-year study – project Aristotle and was found to underpin the other four key dynamics: dependability, structure and clarity, meaning of work and impact of work.

It is known that when workplaces offer a high degree of psychological safety good things happen- mistakes are reported quickly so prompt correct action can be taken, coordination and communication across groups is good and ideas are shared. When there is psychological safety team members feel confident that no one on the team will embarrass or punish anyone else for admitting a mistake, asking a question, or offering a new idea.

What happens when we don’t have psychological safety?

When we experience stress or fear at work, our amygdala is activated (the part of our brain that is responsible for detecting threats) this causes a physiological response and hormones are released which prepare us to have to fight, run or freeze, as our brain focuses on this it shuts down our ability to think strategically and shifts our behaviour from reasonable and rational to primal and reactive. Fear inhibits learning, impairs analytical thinking, creative insight and problem solving.

The most common triggers of our stress response in practice include:

Unrealistic workload

Lack of respect

Unfair treatment (especially following an adverse event or near miss)

Not being heard

Being unappreciated

What are the benefits of psychological safety?

- We know that feeling SAFE TO SPEAK UP creates a positive emotional state which in turn creates a state of trust and curiosity and causes the release happy hormones like dopamine and serotonin which have been found to:

- Improve our cognitive ability. The brain has been found to be 31% more effective in thrive state compared to neutral or survive state.

- Improve our ability to learn and remember new information

- Broaden our minds

- Improve resilience and persistence and enables us to build personal wellbeing resources.

- Enables us to share ideas for innovation, improvement and advancement and talk about error in a safe environment.

All these things contribute to improved team performance and reduced error which ensures that patient safety is maintained.

How to build psychological safety?

To find out more about how you can build psychological safety in your workplace and make sure that every member of the team feels #safetospeak up why not join our upcoming Psychological Safety Masterclass? Email hannah@vetled.co.uk for more information on how to book.

Want to support our campaign AND remind your team of the importance of working towards psychological safety? Download our practice poster using the button at the top of the page!

Campaign Summary

The Aim

The aim of the VetLed Civility Saves Lives Campaign is to raise awareness about the importance of civility and focus on the positive steps we can take to reduce the frequency of incivility in veterinary practice.

The VetLed Civility Programme offers practices in-person bespoke training to support your whole veterinary team.

The Facts

The “Behaviour in Veterinary Practice” Survey (2017) by vetsurgeon.org and vetnurse.co.uk found:

- 73% of respondents have been belittled in front of other staff

- 65% of respondents have been criticised minutely

- 54% of practice managers have been shouted or screamed at

- 48% of nurses have felt deliberately excluded or ignored

Incivility is defined as rude or unsociable speech or behaviour.

The most important thing to remember is that rudeness is defined by how the recipient interprets it, regardless of the intent.

Rudeness can take many forms — it can be insidious or blatant and may include:

- Verbal aggression

- Blaming

- Inappropriate humour

- Closed body language

- Public humiliation

In another survey of doctors and nurses, 75% identified bad behaviours within their teams that led to medical errors, and 25% believed these behaviours contributed to patient deaths.

Why We Are So Passionate About Civility

We often feel that rudeness and incivility are “just part of the job” in stressful workplaces.

However, developing civility is critical to performance and patient care.

Porath and Pearson (2013) found that:

- 80% of recipients of incivility lose time worrying about it afterwards

- 38% deliberately reduce the quality of their work

- 78% reduce their commitment to work

Civility really does save lives.

In leadership, we must consider the wider impact of incivility — clients may be 75% less enthusiastic about an organisation after witnessing incivility.

It Matters for Teams

Rayner:

25% of bullied victims and 20% of witnesses leave their jobs.

It Matters for Clients

With the veterinary profession facing significant recruitment issues, it is vital that we take active steps to reduce incivility.

It Matters for Practices

Healthy workplace culture improves retention, morale, and client satisfaction.

The Solution: A Balanced Approach

Individual

- Make an effort to adopt and exhibit civil behaviour as a non-negotiable part of our character.

- Ask yourself: “Could what I am saying be interpreted as rude?”

- If yes, apologise — even if only to avoid being misunderstood.

- Be aware of the impact of your thoughts, actions, and words.

- Acknowledge your responsibility to ease others’ experiences.

- Call out incivility with compassion.

Team

- Excel in teamwork to reduce external stressors that may lead to incivility.

- Nominate a civility champion.

- Get your team bought in — explain why civility matters to them.

- Discuss the topic at practice meetings or during lunch-and-learn sessions.

Organisation

- Avoid employing individuals who have exhibited uncivil behaviours in the past.

- Consider adopting a zero-tolerance policy.

- Ensure disclosed core values are upheld.

- Book a VetLed Civility Programme workshop.

- Download and display free posters to reinforce positive culture.

What Can I Do?

We believe the VetLed Civility Saves Lives Campaign will have a positive impact on your team.

It aims to help establish a culture in which all members feel safe at work — where everyone supports each other to perform at their best and provide the highest level of patient care.

Positive team dynamics and healthy relationships are essential for high-performing veterinary teams. Tackling incivility is critical to achieving this.

Every practice is different — please consider how to apply this campaign safely and effectively in your workplace.

Download our Civility Saves Lives practice poster by clicking the button at the top of the page!

For more information or support, contact info@vetled.co.uk.

Every April, we run our Veterinary Human Factors Awareness Week campaign. During the week, we give an introduction to the basics of Human Factors principles, including how our behaviour and performance are impacted by the people and the environment around us, how we're feeling on the day, our clinical skills, our non-technical skills, the systems and processes we use at work, and the equipment and resources we have. There are so many interactions that influence the outcome of the work we do, and therefore patient safety. The campaign encourages veterinary teams to get curious about the value of non-technical skills and Human Factors training on their performance, and spread the word about the impact of improved workplace culture, team wellbeing, communication, leadership and team dynamics on patient safety and the people in our profession.

Throughout the week, we share research and evidence that demonstrates the importance of Human Factors training, run webinars and social media polls, and encourage discussions within our community and further afield. We also regularly run giveaways or offer promotional discounts on our bitesize e-learning course 'An Introduction to Veterinary Human Factors'

If you'd like to support our campaign, download our practice poster using the button at the top of the page and watch this space for our 2026 campaign dates.

A simple tool that puts a spotlight on the physical and mental elements that commonly affect wellbeing and performance.

What is HALT?

HALT is a self-care acronym and reminder to pause — to plan and prioritise the daily breaks we all need. It highlights the key factors that can negatively affect wellbeing and performance:

- Hungry and/or Thirsty

- Angry and/or Anxious

- Late and/or Lonely

- Tired

These states make us more vulnerable to errors and stress. Recognising and addressing them helps improve focus, safety, and overall team performance.

Background

Inspired by a campaign from Guy’s & St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust, VetLed adapted HALT for the veterinary profession, recognising that vets experience similar pressures as human healthcare workers.

In collaboration with Dr. Mike Farquhar, Consultant in Sleep Medicine, the campaign reinforces the importance of physical and mental wellbeing in veterinary teams. VetLed’s vision is to inspire, create, and champion positive veterinary culture — for people, patients, and the profession.

“Unless critically ill patients require your immediate attention, our patients are always better served by clinicians who have had appropriate periods of rest during their shifts.”

— Dr. Mike Farquhar, Guy’s & St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust

Why HALT Matters

The HALT factors directly affect how we feel, function, and perform — influencing both patient safety and clinical quality. HALT encourages veterinary professionals to prioritise their own wellbeing alongside their patients’.

Self-care is anything but selfish.

The Three Ps: Plan, Prioritise, Pause

Implementing HALT effectively means making breaks part of daily structure:

- Plan – Schedule team breaks at the start of the day. Hold each other accountable.

- Prioritise – Short breaks improve performance, safety, and morale. Recognise HALT factors early.

- Pause – Actually take your break. Support each other. Leaders should lead by example.

Teams that are not hungry, tired, or anxious perform better, safer, and more productively.

How to Do It

Morning Huddle: Start each day with a short discussion involving the team to set expectations, share concerns, and build accountability.

Break Planning: Map out breaks early to make workloads more manageable.

Accountability: Check in with yourself and others — are you taking your breaks? Leaders can reinforce the culture by modelling this behaviour.

Conclusion

The HALT Campaign promotes simple, actionable steps to improve wellbeing and reduce error through rest, self-awareness, and teamwork. By embedding HALT into daily practice, teams build a safer, more supportive workplace culture.

For more information, visit vetled.co.uk or contact info@vetled.co.uk.

Follow: @VetLedteam on social media.

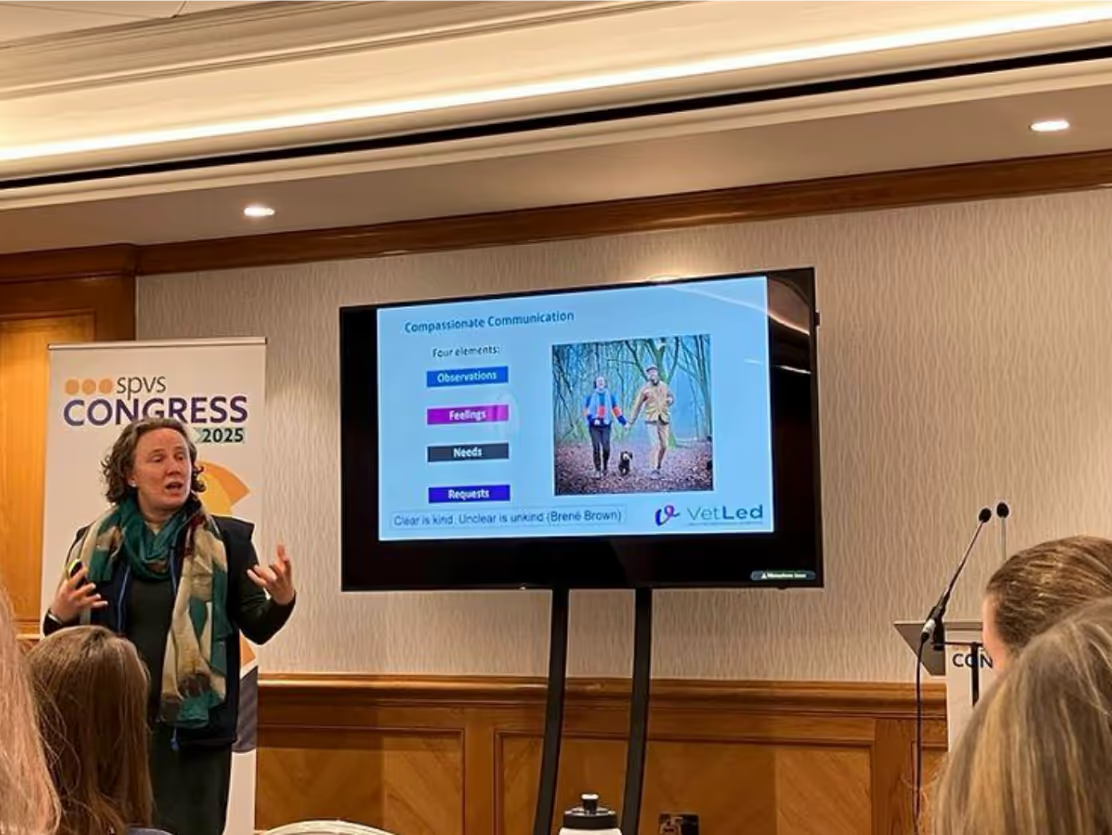

The last session on a Friday might be considered the graveyard slot by some, but for those fortunate enough to attend the workshop on ‘Managing Difficult Conversations with Clients’ from Sara Jackson of VetLed, it proved anything but.

Using principles of Nonviolent Communication, Dr Jackson encouraged a pause before responding in tricky or potentially threatening client interactions. Delegates were taught the framework of ‘observation, feelings, needs and requests’, a way of using ‘I’ statements to humanise the interaction between two seemingly opposed people that is much more likely to result in a civil and positive outcome.

The concept of being civil and polite is part of the VetLed ‘Civility Saves Lives’ campaign, which itself is part of a broader movement within healthcare globally looking at tackling incivility in the workplace. Evidence shows that being involved in or observing rudeness reduces feelings of safety for team members and ultimately negatively impacts patient care, and Dr Jackson illustrated this point with examples from her own career as an ECC advanced practitioner.

The interactive workshop allowed discussion of experiences with difficult client interactions with the opportunity to reflect on these with the example of the non-violent communication framework. The general consensus was that not only would this benefit work relationships but those at home too; one attendee happily stating that this had revolutionised his relationship with his wife!

The session finished with the acknowledgement that as vets, our feelings in the interactions were as important as the clients, an essential point as we look to combat the crisis of burnout in our profession. The hope is that with the practice of this communication strategy the escalation of potential conflict can be halted, and delegates left the session feeling buoyed by this new knowledge.

Please visit https://www.vetled.co.uk/civility for more information on this subject, and www.vetled.co.uk/book-online to find out how VetLed can help your practice team.

(This blog was first published on our previous website)

Our fifth Veterinary Human Factors Conference is challenging veterinary professionals worldwide to take a regenerative and restorative approach to veterinary practice

The overarching theme of our 2025 conference is how to make veterinary work sustainable, creating teams that can reliably work at their best, feel positive about work, and feel supported and valued by their team.

The newly released programme has three streams, each tailored to a group of delegates:

Stream 1 – Introduction to Human Factors

In the first stream, VetLed founder and Training Director, Dan Tipney will be joined by guest speakers, including Emma Tallini, Becky Jones, Sara Jackson, and Crina Dragu, vets and nurses with long experience in this area in practice, education, referral, and first opinion. These Human Factors champions will help delegates understand how they can make a difference to the way they work using tools and techniques that are proven and established in human medicine and other safety-critical professions. The key aim of this stream is not just to help delegates understand what Human Factors is and why it is helpful in veterinary work, but to make sure that they leave with tools and practical tips to form an action plan that applies to their practice, organisation, or team. These tools don’t just improve patient safety, which is an obvious priority in our caregiving profession, but they also help vets, nurses, and other veterinary staff feel happier and more confident at work, working more efficiently and safely, and achieving better wellbeing.

Stream 2 – Knowing Me, Knowing You

I'll be co-hosting the second stream with passionate human behaviour expert and impact-maker Katie Ford, taking delegates on a journey to understand themselves as humans, acknowledge and accommodate their own needs and the needs of others, and work better as a team. It’s so common in the veterinary profession for us to put our heads down and get on with the job in hand, but a wider understanding of ourselves and others as humans can make work a much happier place to be. We'll be joined by Vet Empowered, Petra Agthe, VetYogi, Affinity Futures, and VetLed’s Jenny Guyat, who will each share their unique slant and perspective on an aspect of self-awareness, compassion, being curious, and team dynamics. Together, they’ll share the science behind how our brains and bodies work, how we develop and sustain relationships, and how this affects how we feel and work as a team – giving delegates the power to change their experience of work for the better, and not just for them, but for the whole team.

Stream 3 – Delving Deeper

The third stream will be hosted by VetLed Managing Director, Cat Auden, and a Chartered Psychologist, Ergonomist, and Human Factors Specialist. Stream three allows delegates who are already familiar with Human Factors concepts to think big, share ideas, and shape the veterinary profession. With short TED talks from Suzette Woodward, Elly Russell, and Emma Cathcart, each followed by Q and A sessions, the stream will be highly interactive, encouraging collaboration, thought, and innovation.

Amanda Joy Oates - Cultivating Restorative Cultures, "helping you find joy at work". Board Director of Restorative Justice Culture Foundation

Keynote Speaker – Amanda Oates BA (hons), MSc Strategic HRD, C.C.I.P.D.

Restorative practice means better experiences for veterinary people, patients, practices, and the profession. The concept of restorative veterinary practice relies on establishing a restorative workplace culture, an area that the Veterinary Human Factors Conference 2025 Keynote Speaker, Amanda Oates is passionate about. Amanda was Chief People & Culture Officer and Deputy CEO at Mersey Care NHS Trust, and now runs her own HR consultancy around cultivating restorative cultures.

Previous conference feedback:

‘Really enjoyed the networking sessions, this was a great opportunity to share learnings, alongside the lectures which were great with a huge variety of content. Absolutely fantastic conference again, well done to the VetLed Team!’

2024 Delegate

‘I was absolutely blown away by the event. I’m 20 years qualified and never done any non-clinical CPD or really considered human factors. I recently had a period of burnout due to high workload, hormonal issues and lack of self-care. My practice manager booked me on the conference and I had low expectations. I have had multiple light bulb moments. I’m still working my way through the content but I’m so inspired by everyone that I think this could have unlocked a new passion in me.’

2024 Delegate

Here's what Cat Auden had to say about the conference:

“I’m so proud of how the VetLed conference uniquely addresses the critical intersection of clinical excellence with the science of how humans work. We seek to equip attendees with practical tools to enhance all angles of human performance and wellbeing ultimately resulting in better patient outcomes.

At VetLed, we know that investing in Human Factors training is the key to building sustainable, high-performing teams and delivering the best possible care to both animals and their owners. Every year I love witnessing delegates’ ‘lightbulb moments’ at the conference, as they discover eye-opening, fresh perspectives and practical strategies that genuinely transform the way they work back in their practices."— Dr Cat Auden MRCVS, Managing Director, VetLed

You can book a discovery call at https://vetled.co.uk/book-online or find out more about the conference at https://www.vetled.co.uk/conference

This blog was written by Vasiliki Bitou DVM MRCVS on behalf of the VetLed team.

A scenario where all employees return from work happier than they came in the morning is not a dream, it's achievable. But, as leaders, where do you start?

There is a correlation between happiness and engagement in the workplace. Happiness brings emotional energy but can lead to unfocused employees. In contrast, engagement brings purpose and clarity but can create a competitive environment. The key is balancing happiness and engagement to achieve a productive and positive workplace. After all, no practice will be successful in the long term without prioritising team engagement.

In this blog, we explore how to keep your team engaged with company values and happy at work.

Connecting with the Bigger Picture

One of the main reasons employees in the wider world of workplaces feel disengaged is because they are only involved in specific parts of the production process and not engaged with the final product. This can make their work feel fragmented and less meaningful. In the veterinary profession, we are fortunate because most employees are invested in the patient from start to finish. This direct involvement in the outcome is a unique advantage. However, to take engagement one step further, it is crucial to proactively remind each employee of the vital role they play in the overall process. Each team member should understand where they fit in the bigger picture and why their job matters. The higher their level of engagement, the better their job satisfaction.

Establishing the worth of every employee and justifying why their job is unique is the first step, but the next step is empowerment. Allowing your team to make decisions gets them involved. It is not about telling them how to do things - "your way" isn't the only way. Although letting your team make mistakes and learn from them might feel risky and uncertain, even as an experienced manager, being supportive, approachable, and withholding unnecessary judgement, thereby creating a psychologically safe workplace will promote individual and team growth. Creating plans and problem-solving is essential for feeling productive, involved, and engaged.

Quality coaching

‘As a leader, your role is to engage your team not only in identifying the problems but in thinking about solutions.’

Employees need regular one-to-one meetings, including performance reviews, opportunities to receive recognition as well as, foundationally, building strong working relationship with senior members of the team. Remember that your team members experience any problems and inefficiencies with practice life first-hand. Acknowledging their ideas and validating their perspectives helps to nurture your relationship and positively changes your practice culture. On the other hand, not allowing your team to express their struggles, irritations and, on the flipside, their ideas, will frequently lead to poor team wellbeing, burnout, and loss of staff. As a leader, your role is to engage your team not only in identifying the problems but in thinking about solutions. Their problem-solving skills are like muscles - the less they’re used, the weaker they become.

Beyond the Payslip

Salary is important, but a good salary alone won’t guarantee happy, engaged, and productive staff. In this modern world dominated by specialisation and competitiveness, employees want to grow and develop their knowledge and skills. Providing clear and constructive feedback and ensuring that employees understand areas for improvement and how they align with company values and goals is crucial. Additionally, offering CPD and training opportunities is essential, including vet and vet nurse professional development and non-clinical team members’ training programs. Creating ‘guidelines’ to promote work-life balance (e.g., no emails after work hours) and ring-fencing time inside work for breaks, and outside of work for socialising, hobbies and rest is important to foster team spirit and improve mental health.

The Next Step

Working within the veterinary vocation requires those who practice to bring a great deal of themselves to the job. With that comes vulnerability and the need to prioritise our wellbeing, but it also gives us the power as both leaders, and as employees, to shape the future of the profession we love. If you’re a leader who wants a happier, healthier, and more productive team, join the VetLed Leadership Programme. which is now available to individuals as well as groups of leaders from the same practice. Find out more at www.vetled.co.uk/leadership.

What makes a good leader? – Summary

- Balance team happiness and engagement to increase productivity and improve workplace culture

- Help your team see their role in the bigger picture – share your vision

- Empower your team to make decisions

- Support your team to grow following mistakes, without judgement or shame

The Perception of Time in Our Profession

Time is a curious thing, especially in the veterinary profession. How often do we pause during our ten-hour workdays to consider our progress and what we’ve achieved? By the end of the day, we might not even remember how many people and animals we’ve helped and interacted with, or the details of what happened. Was Charlie the dog or the cat? Did they have the corneal ulcer or the UTI?

Day-to-day life in the veterinary industry can be hectic, and over time, this can contribute to fatigue and mental health challenges. This article explores how we perceive time in a high-pressure environment and the potential effects on Patient Safety. It also offers strategies to make the most of our time at work and highlights the benefits of taking a break, both at work and outside of it.

Time Flies: Losing Track of Time

Time Perception: From Pressure to Purpose

In the fast-paced world of veterinary care, time often feels like an enemy. But what if we could shift our perception of time, turning it from a source of pressure into an opportunity for qualitative improvement? Whilst this may seem at odds with 15 or 20-minute consult slots, there’s value in slowing down, becoming more conscious of our actions, actively interacting with clients and seeing our work not just as a series of tasks, but as a form of care and nourishment for ourselves. Setting targets throughout the day that focus on good care of self as well as good patient care will help keep you focused and prevent overwhelm.

As our profession has a caregiving nature, it’s essential to first care for ourselves and our teams. If we don’t, we’re less able to truly help those who rely on us. We don’t need to be perfect machines that produce diagnoses; instead, we should strive to be natural and, crucially, to educate our clients about what they should expect from the process.

The Relativity of Time in Veterinary Practice

How long has this dog been under anesthesia? How long have we been unable to intubate for? How much time has passed as I try to take blood from this anxious cat? Every veterinary professional has experienced the relativity of time—where minutes stretch or shrink depending on the task at hand. As task-oriented individuals, we often focus on completing tasks at all costs, which can sometimes have catastrophic consequences for our patients.

Take the story of Elaine Bromiley as an example. She went into the hospital for a routine sinus operation and during anaesthetic induction, major complications arose. Her airway obstructed and the team was unable to gain a secure airway. For 20 minutes they attempted to achieve a stable airway, during which time her oxygen saturations were around 40%., Though she survived the initial crisis, Elaine suffered severe hypoxic brain injury and, 13 days later, her life support was turned off.

This tragedy highlights how time pressure and communication breakdowns can lead to fatal outcomes. Elaine's story demonstrates an opportunity for improvement via a Human Factors approach, including the use of systems and processes and fostering psychological safety in the workplace, to prevent these kinds of incidents.

Efficiency of Time

In a time-pressured environment like veterinary practice, systems and processes are key to improving efficiency and reducing errors. Tools such as checklists, safety protocols, and structured handovers are invaluable—although often viewed as an extra burden when first introduced.

Despite being a piece of paper, checklists are so much more. They are simple, easy to follow, and evidence based tools that can significantly improve team coordination. They ensure that a large group of staff can work together smoothly, even under pressure, while keeping adverse event rates low.

According to the WHO checklists study, in 2010 in hospitals in both high and lower income settings in eight cities around the world: "Analysis shows that the rate of major complications following surgery fell from 11% in the baseline period to 7% after introduction of the checklist, a reduction of one third. Inpatient deaths following major operations fell by more than 40% (from 1.5% to 0.8%).”

Checklists and similar tools turn autonomy into heteronomy

While autonomy requires individuals to make their own decisions, the collective nature of veterinary work demands a more structured approach. We all experience unreliable memory recall and limited attention spans, especially in stressful, complex environments where multiple tasks must be managed simultaneously. This reality increases the risk of overlooking critical details, potentially leading to serious consequences.

Moreover, when managing large volumes of tasks - such as the reality of the prep-room: Four inpatients, an animal under general anaesthetic, and members of staff looking for guidance in three different tasks- it's easy to omit basic but crucial safety steps. Even highly experienced professionals are prone to making mistakes. In fact, their expertise might make them more likely to overlook details, believing they can handle any situation. Heteronomy, through tools like checklists, helps to account for human limitations by providing external guidance. Though checklists may initially seem monotonous, patronising and time-consuming, they ultimately save time by providing a clear strategy, assigning specific roles and improving team collaboration.. These tools have been found to enhance efficiency, reducing the likelihood of mistakes that could require significant time to correct—or worse, be irreversible.

How to Escape Time (using Human Factors tools)

How often do you feel the need to step away, take a break, and reboot your system? In the fast-paced world of veterinary care, we have all experienced the feeling that time cannot wait. While we can’t always control the flow of time, we can change how we approach it.

Consider the concept of HALT (Hungry, Angry, Lonely, Tired). While these states seem straightforward, it can be easy to ignore them. The instinct to achieve our goals often outweighs the logical need to stay hydrated, take breaks, or address stress. This can contribute to a workplace culture of “pushing on regardless”, and is compounded when teams witness leaders or colleagues skip their breaks. But recognising these needs, communicating them, and taking a break is crucial. It is absolutely okay to pause and recharge.

Time Off Work

We can't operate at 100% all the time. It's important to accept that it's perfectly fine to enjoy down-time when you’re off the clock. Rest is a valuable tool and essential to our wellbeing and performance. Our brains are highly adaptable, and while they might struggle to slow down after a high-paced day at work, neuroplasticity allows us to retrain our minds to truly relax. Whatever relaxation means to you—whether it's reading a book, taking a walk, or simply doing nothing—it’s vital to embrace it without guilt. Remember, there’s no right or wrong way to spend your time.

Help your team use their time ‘well’ – make wellbeing a priority

VetLed’s HALT resources are a great way to promote wellbeing within your team - with posters and other tools to act as reminders and conversation starters. If you’re interested in implementing HALT, but daunted by the task of changing a well-established workplace culture of ‘just getting on with it,’ let VetLed support you to create the change you’d like to see. Browse our veterinary team training workshops, including wellbeing and culture topics, book an in-practice workshop on Human Factors foundations to help get your team on board, or use a practice observation day to find the best areas to focus.

(This blog post was first published on our previous website)

Last Friday, the 11th of October, we were again joined by curious and passionate individuals from the veterinary community, at the Veterinary Patient Safety Summit 2024. For our third year running this event, we were aiming high. After all, to make a real positive impact we need to spread the word out into frontline practices, as Cat Auden said in the welcome session:

‘Once we can get 45% of the veterinary population saying “Yes, this matters”, we know we can make a real difference.’

Cat Auden, VetLed

VetLed Managing Director, Cat Auden, welcoming delegates at VPSS 2024

Therefore, we wanted to meet new patient safety champions and benefit from the insights and experiences of those leading the field. So, when the setting up and morning organisation were done and people started to arrive, we were excited to greet a real mixture of vets and vet nurses from different backgrounds and holding various positions. It was great to reconnect with two vet nurses who had attended VetLed training in April, and we were delighted to meet a range of practice owners from independent practices across the UK and senior corporate leads in Quality Improvement and Clinical Governence. From the moment people walked through the door, there was a real buzz as they greeted old friends and began conversations with new connections. This inclusive atmosphere lent itself to a safe space for all to share, no matter their practice background.

What did the day look like?

The event was held at the Consort E3 Lab, set within Harper and Keele Vet School. This versatile, ultra-modern learning space allowed us real freedom to deliver the sessions however we wanted. It was nice to have a balance of informal, sit-down lectures, with interactive polls and Q and A's, combined with brainstorming tasks completed in rotating small groups. Even coffee breaks and lunch were a time to continue conversations, and this talking time was really valued by the delegates and VetLed team. Hamish Morrin, one of our associate trainers, was brimming with enthusiasm when he shared how much he’d enjoyed chatting to delegates about regenerative and restorative practice.

The Great Veterinary Patient Safety Think Tank

One of the delegates acting as scribe for his group during the Great Veterinary Patient Safety Think Tank

With so many diverse and valued people in the room with the knowledge to share, we knew it was an opportunity to collaborate and contribute to overcoming the barriers to Patient Safety. So, we set up the Great VPS Think Tank, where delegates moved in small groups to different magic wall (Yes, we could write on the wall!) stations, answering the following questions. If you’re running a veterinary practice or organisation, take note:

- One thing I would like to see across the profession that would make the biggest difference for patient outcomes is…

In this discussion, it was great to see where different groups placed their emphasis. For instance, one group focused on the importance of a positive workplace culture, where leaders set examples, hierarchy is shallowed (where appropriate), and openness around mistakes, concerns, and near misses is encouraged or rewarded. The role of standard processes, like checklists, was also highlighted. However, another group felt the key to answering the question lay elsewhere – in commitment to and financial investment in Patient Safety across the profession. A third group added that educating the next generation of vets and nurses was another opportunity for positive change.

- My biggest current challenge with achieving what I want for my patients is…

As you might expect, one of the challenges that came up during this discussion was time or lack thereof. This lack of time prevents appropriate reflection on cases and their outcomes, even though time invested in reflection is recouped later through lack of error and better productivity. Lack of time is also an obstacle to meeting our physiological needs by taking adequate breaks. But this wasn't the only identified challenge. Conflicting goals and mismatched risk tolerance between clients and veterinary staff, the public perception of our profession (fuelled by the media), client behaviour, and differences in communication style between clients and within the team were just a few of the answers our small groups suggested.

- When I think about error, I think about…

The ideas around this question had two main streams. First, the emotional reaction, including 'that gut feeling', self-blame, trauma, and the fear of judgement. However, this was followed by a proactive and positive approach, highlighting the importance of curiosity, a Just Culture, debriefing, and a non-judgemental approach. During these conversations, delegates spoke about the importance of checking in with the person or people affected, using appropriate language and communication styles that avoid blame and shame, and considering the acronym ‘FAIL’ – ‘first attempt in learning.’ Perhaps one of the nicest responses we saw, though, was ‘VDS’ written on the wall, surrounded by a heart – an important reminder to get support and guidance when you need it.

Who were the speakers at VPSS 2024?

Pam Mosedale – RCVS Knowledge

Pam gave a fantastic overview of how we can support Patient Safety in practice through audits and research. She acknowledged the frustration leaders feel when they put effort into creating guidelines, only for them to be ignored. As a response to this, she highlighted the importance of involving the whole team in Quality Improvement efforts when she said:

‘It’s like the man at NASA sweeping the floor – when asked “What do you do?” he replies, “I send men to the moon”’

Pam Mosedale, RCVS Knowledge

Pam Mosedale, from RCVS Knowledge invited thoughts from delegates during her session on the importance of audits and research

Alongside promoting a whole team approach to audits and research, Pam also spread awareness of supporting resources, including the RCVS Knowledge Library, their journal watch system, inFOCUS, international audits, and benchmarking tools.

Catherine Oxtoby – Veterinary Defence Society

We were pleased to be joined by Catherine Oxtoby, from the VDS, who tagged into Pam's session 'Patient Safety – Where's the evidence?' Catherine opened her section by pointing out how far the profession has already come in terms of response to mistakes and adverse events, both in terms of non-clinical topics being firmly on the agenda at vet conferences, but also in how we talk about error:

‘When I messed up in practice, we didn’t talk about it.’

Catherine Oxtoby, VDS

Catherine Oxtoby, from the VDS, shared her enthusiasm for veterinary research with delegates

Since Catherine has moved from clinical practice, there’s been a shift in how we respond to errors. Higher levels of psychological safety mean that mistakes are more likely to be discussed, the people involved asked whether they're okay, and a curious approach adopted to find out what can be learned going forward. Of course, there's still plenty of room for improvement, and different teams will be doing this well, or less well. Finally, Catherine closed by highlighting the benefit of events like VPSS 2024 in bringing practicing vets and vet nurses with a research interest together with current researchers, allowing an opportunity for collaboration and support. She encouraged delegates to get involved in research, inviting them to find what makes them curious or annoyed in practice and use that as a focus for research or audits.

Sara Jackson – VetLed

During her talk, ‘Is Human Error Ever Truly a Cause of an Unexpected Outcome?’, Sara encouraged interactivity via Slido polls. She bravely shared her own experiences in practice, and how they’ve shaped her approach to mistakes within her team, which can be summarised with this quote:

‘Okay, I’ve made an error. What am I going to learn?’

Sara Jackson, VetLed Associate Trainer

VetLed Associate Trainer, Sara Jackson, addressing delegates during her session at VPSS 2024

She highlighted the importance of language, questioning whether the term ‘error’ might perpetuate a blame culture and pointing out that the term ‘unexpected outcome’ is widely understood as a negative when actually, outcomes can also be unexpectedly good! The language theme continued when she acknowledged the barrier posed by the term ‘leader’. Sara pointed out that some people are excellent leaders in practice, but don’t view themselves as leaders, meaning it can be hard to reach them. Using other terms and titles, like ‘Coordinator’ rather than ‘Lead’ may break down this barrier and be helpful for those who don’t self-identify as leaders.

Emma Cathcart – VetSafe

Constructive reporting was the theme of Emma's session. She used one of her own experiences as an intern to demonstrate not only the importance of learning from mistakes as a team but also of sharing this knowledge with others. This prevents new staff from making the same mistake but also means we can learn and progress as a profession, which is really powerful. During her talk, Emma showcased the power of incident reporting by saying:

‘Incident reporting is like a black box recorder. It helps us figure out what was going on in the moment.’

Emma Cathcart

Emma Cathcart, from VetSafe, speaking at VPSS 2024

Incident reporting can be a local, single practice system, like an 'oops book', but it's most useful when this information is reported nationwide, providing data for research and improvements that can be shared throughout the profession and to other safety-critical professions. VetSafe, the nationwide incident reporting system, is relaunching in November and you can find out more at https://vetsafe.org.

Dan Tipney – VetLed

To begin his session on restorative and regenerative veterinary practice, Dan opened by describing a forest – a natural restorative system. The brambles serve to protect fragile saplings, until they grow stronger and overtake the brambles. Fallen trees let more light in and are broken down, feeding into the soil and providing further opportunities for new growth. This process of continually renewing itself can be applied to veterinary practice too, and is particularly applicable to working things through after an unexpected outcome and going forward afterwards. However, Dan pointed out that it takes a commitment to restorative actions, including addressing imbalances caused by not meeting the needs of the team, but there needs to be a balance between learning and accountability.

VetLed Training Director, Dan Tipney, contributing to conversations at VPSS 2024

‘Who is to blame is not a particularly helpful place to start when something goes wrong. Instead, ask “How do we stop that from happening again?” ’

Dan Tipney, VetLed

Further questions suggested by Dan that should be posed when faced with mistakes or adverse events include:

- Who was hurt?

- What do they need?

- Whose obligation is it to meet that need?

By asking these questions, it puts the focus on rebuilding and repairing, creating motivation for positive action, and providing support. Dan provided realistic actions that could be implemented in practice, like Schwartz rounds, celebrating and understanding success, surveys, focus groups, and changes in language toward 'non-routine event' or 'event' rather than 'error' or 'adverse event.' In turn, these actions improve team wellbeing and satisfaction, as well as providing opportunities to look closer at the way we work and make improvements. Finally, Dan closed his session by highlighting the potential of restorative veterinary practice and its benefit to people, patients, practices, and the whole profession.

The power of conversation

Aside from the knowledge gained during the organised sessions, the value of tips and snippets shared during informal conversations throughout the day cannot be underestimated. So many delegates have praised the format of VPSS 2024 and how it facilitated learning from everyone in a safe and inclusive space.

What was the feedback?

The feedback that we have received has been overwhelmingly positive. Not only are people celebrating the power of meeting in person at VPSS 2024 and the work that we are doing at VetLed, but they are also sharing the changes that they’ve already made as a result of attending. Here is just a small sample of the feedback we’ve had already:

'My 1st and 2nd year tutorial groups started with Gratitudes this morning (and a chat about Human Factors and Civility Saves Lives). Thanks for the inspiration, Fiona Leathers.'

Jenny Powell, HKVS

'I've come away feeling so much more positive about the veterinary industry. I found myself saying 'That makes me so happy!' many, many times when listening to what people are doing in their work.'

Steph Ivers, Sunflower Veterinary Services

‘Another amazing event by VetLed!’

Louise Grieve, Veterinary Specialists Scotland

‘As with previous VetLed stuff, it has given me more/renewed enthusiasm to take the Human Factors/QI/Patient Safety stuff and keep it going in the practice’

Katie McCreary, Hook Norton Veterinary Group

What next?

Whether you attended VPSS this year or not, we know you want to create better experiences for the vets, nurses, and non-clinical staff you work with - not to mention your patients!

If that's you, visit https://vetled.co.uk/book-online to book a discovery call with one of our team, and let us help you find training that suits you.

Don't forget that we offer:

- Training workshops

- Observation days

- A Leadership Programme

- The Veterinary Human Factors Conference 2025

We hope to see you all at the Veterinary Patient Safety Summit next year!

When asked what makes a high-performing team, what would you say? I’m sure many people would say that having the best skills or most talented individuals on the team would lead to the best performance.

However a massive study conducted by Google in 2015 showed that:

“who is on a team matters less than how the team members interact, structure their work, and view their contributions”[GOO19].

So in the veterinary context, our clinical skills and combined IQs can only get us so far in terms of performance as a practice. We hit a metaphorical performance glass ceiling.

The study at Google demonstrated that 5 key factors set the most successful teams apart from the others.

- Psychological safety – can team members take risks without feeling insecure or embarrassed?

- Dependability – Can team members rely on one another to do high quality work on time?

- Structure and clarity – Are goals, roles and execution plans clear for our team?

- Meaning of work – Is our work something that is personally important for each of us?

- Impact of work – Do we believe that the work we’re doing matters? [GOO19]

So the number one factor present in a high-performing team? Psychological safety. And furthermore, this factor underpins each of the subsequent four factors.

What Does Psychological Safety Mean?

Psychological safety is the creation of an environment in which all team members are safe, and feel safe, to take interpersonal risk to speak up without fear of judgement or animosity from colleagues.

This may be with a new idea, halting a process that may be dangerous, admission of a need for help, offering constructive feedback or adding opposing opinions to a discussion no matter what level of the team hierarchy the contributor is, amongst myriad other things. Data from Gallup [GALL17] polls show that in the US, only 3 out of 10 workers feel it is safe to speak up at work. But there is hard data showing that productivity and turnover increase (12% and 27% respectively) and safety incidents drop (by 40%) simply by increasing how many workers feel their opinions matter. As a high-performance workplace and as a business we are losing enormous value if our team don’t feel psychologically safe.

“If we’re not hearing from people we may be missing out on a game-changing idea…or we might miss an early warning…that someone saw but felt unable to bring the bad news to their boss.”

So how does a team create an environment of psychological safety? Is it as simple as being led by someone who is nice, kind, humble, helpful and authentic? Well in short, no. Building psychological safety and trust in a workplace isn’t as simple as just being the ‘nice guy’. Research has shown that there is greater trust when we identify with people in the same group, particularly if the purpose of the group is something we care about fundamentally. Hence the way that points 4 and 5 above underpin the level of psychological safety in our own veterinary workplaces. Do our team members feel that the work they do as individuals is personally important to them? Do they believe that the work they are doing matters? If as a team we are all feeling the same about these issues, then an environment of psychological safety starts to build.

The following statements were used by Prof Amy Edmondson (who coined the term psychological safety) to survey how employees felt about the psychological safety in their team. What would you answer?

How Does Psychological Safety Relate To Just Culture?